At least since the first Taoist masters cavorted in China’s misty mountains, people have been trying to find ways to live more authentic and joyful lives. They have been trying with varying degrees of success to work out just what it takes to be free.

At least since the first Taoist masters cavorted in China’s misty mountains, people have been trying to find ways to live more authentic and joyful lives. They have been trying with varying degrees of success to work out just what it takes to be free.

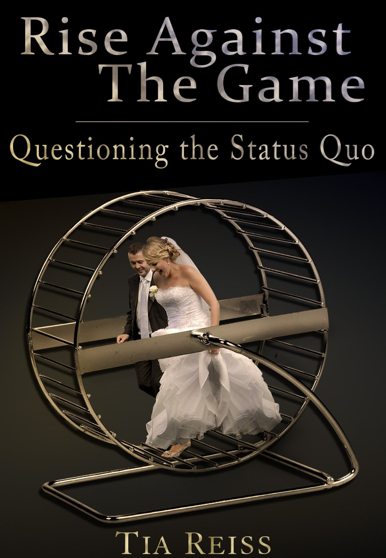

In this short, punchy essay, Tia Reiss, a certified yoga teacher, meditation teacher, and Reiki Master, who describes herself as a mystic and a scientist, argues that we are all naturally equipped with the ability to live authentic lives, but are constrained by social rules, expectations, and judgments. She calls these constraints The Game. The Game, argues Reiss, uses fear and a desire for conformity to keep individuals from living freely and in accordance with their true natures.

The essay starts off a bit muddled, seemingly unsure if it wants to be a spiritual or political tract. However once Reiss begins discussing domestic relationships, she really hits her stride. In fact, I might argue that a reconfiguring of domestic relationships is what this essay is essentially about. The other points are just a way to build up to this, or perhaps an attempt to ready the reader for her suggestions. Reiss nicely sums up the history of marriage:

For most of human history, marriage was a union of practicality, economy and politics. It was an arrangement that united particular families, strengthened political and religious affiliations, and had nothing to do with love. Further, the feminine had very little, if any, rights or choice in the matter. You married who you were told to marry, and that was that. Marriage was a structure that was in place for reasons other than love and life partnership based in real connection.

However, Reiss seems to have missed a lot that has happened since Betty Friedan. Reiss describes domestic relationships in a way that seems more like the relationship between Ward and June Cleaver than the vast majority of contemporary couples:

So we have the masculine stuck in the role of provider and protector, and the feminine in the role of needing to be protected and comfortable.

Reiss makes clear that by “masculine” she does not necessarily mean male and by “feminine” not necessarily female. However, the fact that she has to point out this distinction is an indication of how much things have changed. Men and women/women and women/men and men may have all sorts of difficulties working out the roles and power structures in their relationships, but I don’t think the masculine as provider and the feminine as dependent other, as Reiss suggests, is any longer a common paradigm. Nonetheless it is worth considering the chilling possibility that it is only economic conditions that enforce a kind of de facto equality in relationships—I certainly don’t like to think so. But if that’s true, it would at least partially explain the abundance of “Princess” literature aimed at young females. I would like to hear more from Reiss on this.

Fortunately Reiss doesn’t stop with simply explaining the problem, whether it is primarily domestic or more general. She offers guidance on how to free oneself from The Game, the keystone of which is abandoning fear and giving up the need to accept the status quo.

Organic connection flows naturally in the absence of fear. It is based on an ongoing awareness of the reasoning behind your decision-making on all levels, a constant questioning in the moment. And it is being wholly present in the intensity of a single moment where connection births itself and flowers, where living in the crest of that wave sustains itself. Being wholly present means dropping out of distraction and constant movement.

While I suspect that few would argue her point, for people truly entrapped by The Game, that advice could do with some unpacking. Simply being told that one should be brave, defy attempts at social control, and approach life with “all senses wide open” is not likely to be much use. Perhaps because it is such a short essay (only 28 pages) and there is so much to say on this topic, the pace seems a bit breathless. I found myself wishing she would slow down and unpack some of her statements. It seems almost a requirement of the genre that the message be delivered in a slow, relaxed manner. If one is to ” . . . step off the rodent wheel. Throw off the roles. Tune in. Knock fear off its pedestal. Step into a new world with all senses wide open,” as Reiss suggests, a bit of breathing space would be helpful. Reiss’s message and her voice are, however, very encouraging. I expect that readers of this essay will be eager to hear more from her.

Links

Amazon

Tia Reiss website

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Publish Your Book | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

Leave A Comment