We all like to love a rogue – or even a criminal mind. But why is it so many self-published authors seem to just get the balance all wrong when it comes to writing an antihero?

The antihero[1] or antiheroine[2] is a leading character in a film, book or play who lacks some or all of the traditional heroic qualities,[3][4] such as altruism, idealism,[5] courage,[5] nobility,[6] fortitude,[7] and moral goodness.[8] Whereas the classical hero is larger than life, antiheroes are typically inferior to the reader in intelligence, dynamism or social purpose[9] – giving rise to what Robbe-Grillet called “these heroes without naturalness as without identity”.[10] Wikipedia

In Jon Gingerich’s piece Writing Beyond the Good/Bad Character Dichotomy, he says, ” …The best characters are usually somewhere in the middle. A well-written “good” character is always a little bad, and a compelling “bad” character is usually a little good.”

As a reviewer for SPR, I read a heck of a lot of self-published work and I keep seeing the same mistakes lately.

It seems clever and more profound to add texture to a story by making our protagonist a real bad seed – Rosellen Brown in the NY Times says, “Stories of malfeasance, starting with Adam, Eve and the serpent, have always been far better, if more provisional, ways than spotlessness of soul to stir an audience to attention and meditation.”

But it really turns readers off if they are too evil. Lately, I’ve had to read about a wife beater, a selfish liar so weak I was pleased when his girlfriend dumped him, and a child molester – none of whom seemed to show an ounce of remorse. Let’s analyze why exactly these main players dirty up their book in all the wrong ways.

Let’s take some of the best antiheros in film and literature.

Travis Bickle in “Taxi Driver“. He’s a mad monkey for sure: paranoid, violent, self-absorbed, maniacal. But he’s served his country in Vietnam. He also loves. He has tenderness for Iris, and passion for Betsy. The reason we end up hating Harvey Keitel’s pimp character Sport is that he has a fondness for Iris in all the wrong ways, and he’s abusive to her. If Robert De Niro’s character had touched Iris at all, Travis Bickle would be lost. If he wasn’t a war hero, he’d be done for.

Another great antihero is Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With The Wind. She’s nasty, selfish, spiteful and lazy – but she’s also immensely kind to Melanie, whose husband she is after, despite her jealousy. She also works hard for her family when their farm is destroyed by soldiers and nurses her father. If she acted despicably all the way through the book, even though she steals men and lies all the time, she wouldn’t be the least bit charming and we wouldn’t care what happens to her.

Jay Gatsby in The Great Gatsby, although a fake, a liar and a grossly vulgar gangster, somehow comes off better than all, when Carraway recounts his last encounter with Gatsby, ““They’re a rotten crowd’, I shouted across the lawn. ‘You’re worth the whole damn bunch put together.” Because Jay Gatsby is a dreamer – a quixotic romantic who loves, with a fatal weakness for the shallow yet beautiful Daisy.

And how about in Chuck Palahniuk’s legendary novel Fight Club? Tyler Durden starts a bare knuckle fighting club that spawns a revolution, leading to death and destruction. He’s split in two parts – an unnamed protagonist struggling to sleep and attend a boring office job, towing the line, and his rebellious maverick friend Tyler. Tyler, played by Brad Pitt in the movie, is so utterly gorgeous and intelligent that his methods seem somehow sane and even inspiring, even when he’s making soap out of rich women’s liposuctioned fat and selling it back to them at inflated prices.

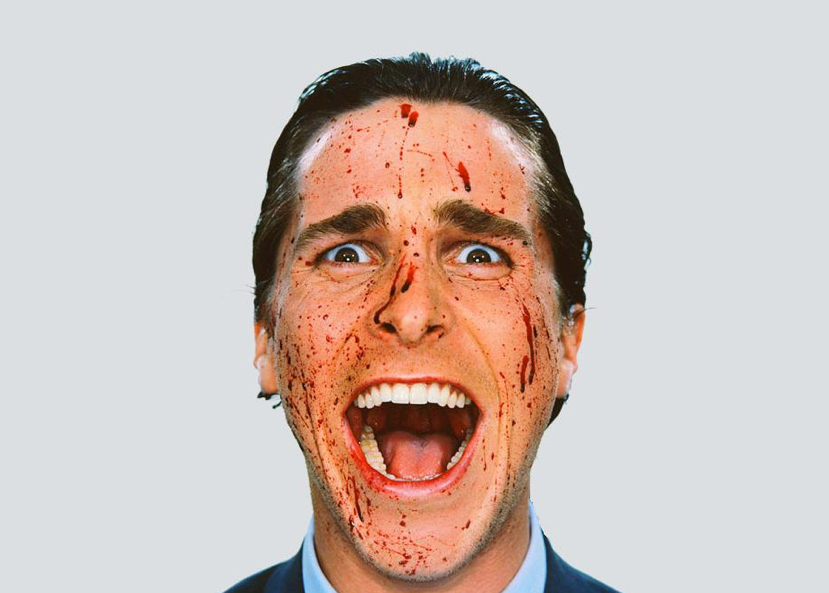

Even in American Psycho and Lolita, despite being insurmountably disgusting in thought, both Patrick Bateman and Humbert Humbert seems distractedly poetic and erudite, with deep soulful reflection on their own demise – even fueled by characters much less likeable than themselves. In Lolita, Humbert is flanked by Lolita’s grotesque mother Charlotte and the horrendous Clare Quilty. Humbert admits in his journals that the death of his teen love Annabel can explain away his hebephilia. Bateman has to contend with a whole bunch of horrid snobs including his work colleagues and even his fiancee. Bateman says of his alienation,” …my normal ability to feel compassion had been eradicated, the victim of a slow, purposeful erasure. I was simply imitating reality, a rough resemblance of a human being, with only a dim corner of my mind functioning”.

Self awareness of shortcomings that lead to weakness, or motivation- not to be evil but to carry out evil tasks that seem somehow absolutely necessary, are the ingredients for a great antihero – without weakness or motivation, characters are flat and lifeless, however evil you intend to make them.

If a character drinks, why do they drink? If a character stalks a young woman or murders her, why does he have to do it? When writing this level of darkness, ask yourself what purpose this act serves for your character. If your characters can’t rouse themselves into changing their life, why? If you don’t know, then your readers won’t know either!

To check up on your characterization, why not check out tvtropes.org to have a look at their “bad writing” crazy characterization section?

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Publish Your Book | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

Excellent,thoughtful post. Thanks.

“an unnamed protagonist struggling to sleep and attend a boring office job, towing the line,”

It should be “TOEING the line.” Yes, I know, a lot of authors get that wrong.

A Palahniuk eggcorn. But thanks.