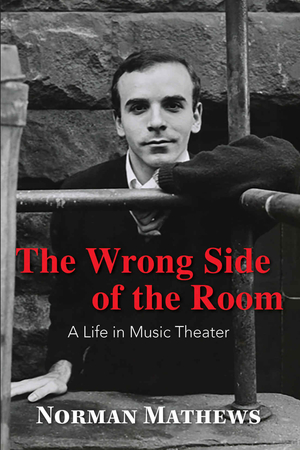

I’ve been telling stories about my Sicilian-American family and my career in musical theater all my life. In my delivery, I always attempted to embody the various characters I depicted—specific accents, vocal cadences, facial expression, and gesticulations. Well, I’m Sicilian for God’s sake; we use our hands to tell stories. Can we even talk without our hands? I doubt it. People seemed to enjoy these anecdotes, but I was never certain whether they liked the story for itself or because of my delivery. If they were just seeing words on a page, would it resonate? For this reason, I was not convinced that I could make the tale as funny or as moving on the page. An example from my book, The Wrong Side of the Room, describes my mother who was both a Mrs. Malaprop and a serial mispronouncer of words.

I’ve been telling stories about my Sicilian-American family and my career in musical theater all my life. In my delivery, I always attempted to embody the various characters I depicted—specific accents, vocal cadences, facial expression, and gesticulations. Well, I’m Sicilian for God’s sake; we use our hands to tell stories. Can we even talk without our hands? I doubt it. People seemed to enjoy these anecdotes, but I was never certain whether they liked the story for itself or because of my delivery. If they were just seeing words on a page, would it resonate? For this reason, I was not convinced that I could make the tale as funny or as moving on the page. An example from my book, The Wrong Side of the Room, describes my mother who was both a Mrs. Malaprop and a serial mispronouncer of words.

We were often subject to such howlers as: “What are you, the Gestapolo?”; “I don’t give one coyote what she thinks”; “Lord and behold”; “Your brother just shruggled his shoulders”; or my personal favorite, “When he showed up at the door, I was just fiberglassted.” Neither she nor her sister Lena could say the word, anxious—it was always antchus—nor could they pronounce words that had “ts” or “tes” endings. Tastes became taysez; costs became caussez; and an often-repeated line was, “She trusses no one.”

Did my audience need to hear the way she assuredly mispronounced these words? This became the first stumbling block to writing my autobiography. (I use the terms autobiography and memoir interchangeably, though I’m aware that memoir is technically the story of a specific period in a person’s life, while an autobiography encompasses the entire life.)

What Will My Family Think?

The second stumbling block concerned my family and friends. For anyone of Sicilian descent to recount family intimacies as honestly as I have tried to do in The Wrong Side of the Room would be unforgivable sacrilege. Sicilians live by a code, bella figura, which basically says that what happens in the family stays in the family. From my parents and grandparents, I heard myriad times, “What would people say, if they knew.” Horrors! Would anyone in my family be able to show his or her face again? Thus I had to wait until my dotage and my parents had passed before I could write about them.

And friends and ex-lovers? Would they ever speak to me again if I shared my uncensored depiction of them with the world? Probably not, though I tried to be as unsparing about my own shortcomings as I was with theirs.

Do I Really Want to Expose Myself?

I knew that I had to be brutally honest about myself or there simply was no point in writing the book. Was I really ready to lay myself bare, letting the world know about my foibles, intimacies. embarrassments. and mistakes? What would this do to my career, to my reputation? Did I even have a reputation? My mortal fear of public embarrassment was a real impediment. These questions stopped me short in my tracks every time I considered writing the book. Thus it took until old age for me to admit, none of this can hurt me any longer. I have nothing more to hide.

Do I Have the Chops?

And finally, did I have the ability to write my own story with a convincing narrative arc and make it of interest to anyone other than people who know me? It wasn’t until I became a playwright later in life that I developed the confidence to attempt it. I knew I had to bring everything I had learned as a dramatist to bear on my writing. I decided to make it as novelistic as possible, with various scenes constructed like short plays. Whenever possible, I used dialog rather than description, and often I switched to the present tense to place readers directly in the scene, giving them the feeling that the incident was happening in the real-time present.

Would Anyone Care?

Who would the audience be for such an autobiography? Musical-theater lovers, those who thrive on celebrity gossip, young gay people who are struggling with their sexuality ( as I did), and those who wish to pursue careers in the arts seemed the most likely targets. What would I have to say to these audiences? To musical-theater enthusiasts, I could offer insights into how theater works are made—their birthing pains, their rewards, and their many disappointments. I had ample gossip about the celebrities I worked with—Barbra Streisand, Gene Kelly, Dorothy Lamour, Michael Bennett—to satisfy those cravings. Surely, my own harrowing coming-out story fits perfectly with today’s “It Gets Better” campaign to stop gay-teen suicide. Though I’m of another generation, much of what I went through still applies today. And for those, who are longing for careers in the arts, my story provides some hard lessons for the difficulties and rewards they might expect to encounter.

Why Do Celebrities Get All the Attention?

Being a celebrity today seems to require that one write a memoir—even if the actual work must be assigned to a ghost writer. These biographies are what the public demands. But what about those of us who never became famous, yet are working professional artists? Many of our stories are just as interesting as our more famous colleagues’ tales, and they deserve to be told. Though we may not be celebrities ourselves, many of us have worked with such people. While I was writing the book, however, I focused on a larger audience than those I targeted. I set as a goal that I would fashion a good story well- told, one that could be enjoyed by anyone who loves to read.

The Big Push

The real impetus to write the book came when I met the editor of the Times of Sicily, Giovanni Morreale. I told him about my new opera, La Lupa, based on the Sicilian writer Giovanni Verga’s novella. He suggested that I write an article for his publication—Journey to a Sicilian Opera. I had so much fun detailing the process. I was hooked. A voice in my head demanded, “Write the book now!”

The experience of writing my autobiography was instructive in many ways. Taking the random stories in my head and organizing them into a narrative, forced me to take cognizance of my life and evaluate it in ways I never before experienced. I know now why so many psychotherapists suggest that their patients write out their stories. It’s a cathartic experience.

Norman Mathews’s The Wrong Side of the Room: A Life in Music Theater is out now.

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Publish Your Book | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

Leave A Comment